Anecdotal Evidence Won’t Help Us Understand Financial Inclusion

An article published last year in Bloomberg was highly critical of the microfinance industry and the international institutions that invest in it. The article described many negative practices—including but not limited to aggressive debt collection—and implied that the microfinance industry is doing serious harm to customers while international, public, investors turn a profit.

While there are, in fact, serious issues in the microfinance sector that need to be addressed—including over-indebtedness, debt collection practices and discrimination—these issues need to be seen in the context of many of the very positive impacts that microfinance is having for clients. And, more importantly, both the negative and positive impacts of microfinance need to be quantified objectively, to better understand the proportion of clients microfinance is working for, and the proportion that it’s not.

This kind of balanced approach is not possible when reporting is done with small scale, largely anecdotal evidence about a complex situation on the ground.

As I have said in the past, social interventions like microfinance loans vary a lot in their characteristics and impact across contexts and periods. It is problematic to use a handful of interviews with clients or “experts” and extrapolate about an entire country or industry from these narrative accounts. And yet, the basis for the article’s broad claims are “dozens” of interviews with microfinance borrowers, along with expert interviews—a radically narrow sample from which draw sweeping conclusions.

What we need is large-scale, objective, comparable customer data to understand what’s really happening for all—and not just a few—customers. In service of these goals, in the last two years, the firm I lead, 60 Decibels, has listened to more than 50,000 microfinance customers in 41 countries, using a single, standardized survey tool that allows for full comparability across all questions. For each institution, we spoke to a representative, random sample of clients, and, in total, these customers represent an estimated 48% of the 173.5 million microfinance clients globally.

We can use insights from this data to cast some light on the murky claims made in the Bloomberg piece.

- Claim: Clients are pressured to sell their homes, land, and other assets in order to make repayments.

- What we found: 19 out of 20 of the microfinance customers we spoke to said that agents treat them fairly, are trustworthy, and have never pressured them to sell an asset.

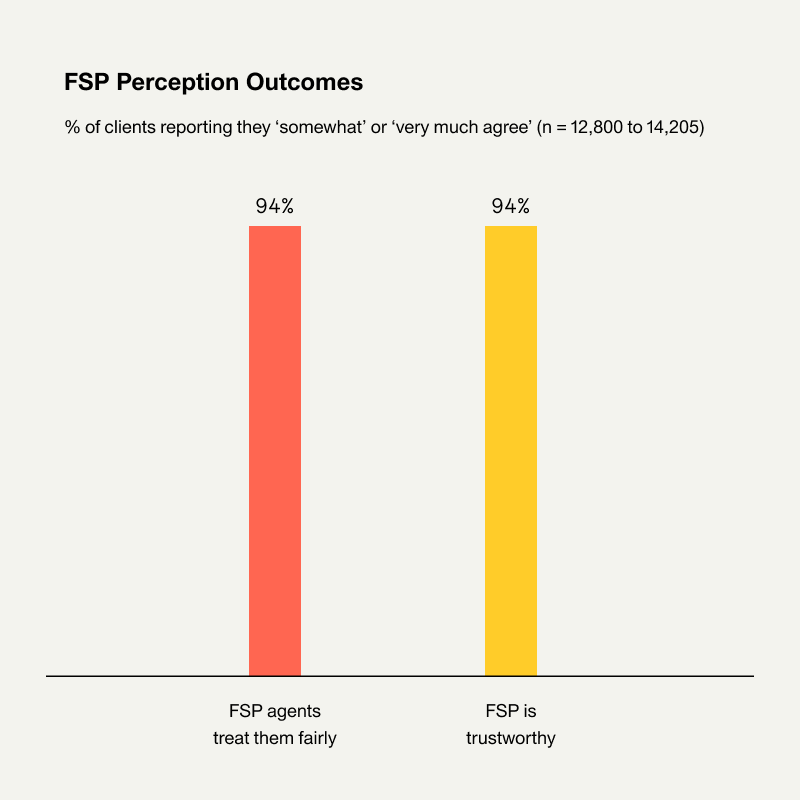

We ask clients whether microfinance institutions treat them fairly and whether they are trustworthy. 96% of clients we spoke to reported not feeling pressured by their financial service provider to sell anything they didn’t want to in order to make a repayment. Moreover, just about as many (94%) reported that they thought their FSP provided them with fair treatment and was trustworthy.

These data don’t mean that negative practices don’t exist. It’s possible that respondents under-report negative behaviors; and, even if they don’t, about 5% of clients are reporting being treated unfairly or not trusting their MFI. That 5% would represent about 7 million clients globally—a very large number indeed, and one that we want to see decrease. It would be very easy to find, in these 7 million clients, terrible stories of aggressive collection tactics by MFI agents. However, our data indicate that this experience is the exception, and not the rule.

- Claim: Clients cannot make their loan repayments, and so they end up in a debt vortex with more than a few loans in order to make repayments – and sometimes that isn’t even enough.

- What we found: The majority of microfinance clients we spoke to say they had no trouble repaying their loan and they have never had to reduce their household’s food consumption to repay. Moreover, they understand their loan terms clearly.

The Bloomberg article tells the story of a baker in Mexico who went through a “vortex of debt” that led to both financial and psychological suffering. This is certainly a worrisome story, and something that should never happen. However, our data indicate that, in most cases, the industry is lending to who are successful at avoiding over-indebtedness. 75% of the people we spoke to told us that their loan repayments are ‘not a burden’ and 83% said they never have had to reduce food consumption because of loans. Moreover, we find that people seeking microfinance understand what they are getting into with loan terms and conditions, with 88% agreeing that they clearly understand them.

Again, like the questions on pressure to repay loans and trust, this is not a 100% good news story. A quarter of clients saying that repayments are a burden is a significant number; and, ideally, we would hope that no one has to reduce their food consumption to repay their microfinance loans. These topics are front and center for the microfinance industry, whose efforts on client protection include the client protection principles (taken over from the SMART campaign) and a client protection pathway and certification from SPTF+Cerise.

- Claim: Microfinance increases worry about finances, leading to unmanageable stress for clients.

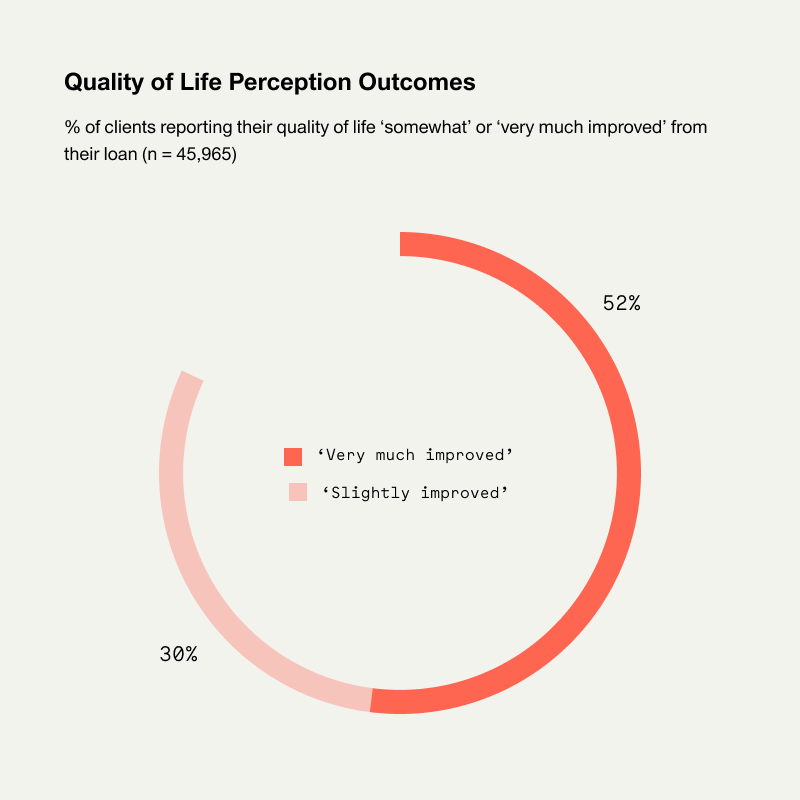

- What we found: Half of the clients we talk to (55%) say that they are spending less time worrying about their finances after their loan, and a quarter said their worry hasn’t changed. 82% report an improved quality of life.

The piece also covers some of the microfinance industry’s most alarming negative outcomes on people’s wellbeing, including waves of suicides in India and Sri Lanka in recent years. Again, these negative outcomes are shocking and they are cause for alarm, but we have to see them in the context of the improvements in wellbeing that are reported by 4 in 5 of the clients we spoke to.

I want to be clear about the conclusions I draw from our findings, and avoid falling into the trap of overly-broad generalizations. Our data provides a nuanced view of microfinance, and leads me to the conclusion that microfinance delivers positive outcomes for most customers, with a wide variation in the strength of these outcomes and with a meaningful amount of negative outcomes in some cases. It’s not all good news, it’s not all bad news.

Having worked with many of the leading investors and microfinance institutions in the sector, I can personally attest to a deep focus on mission, a willingness to learn, and a desire to improve. Rather than be fooled into thinking that microfinance is always good all the time, or to read a worrisome expose and decide that microfinance is fundamentally damaging to most clients most of the time, the truth seems to lie in the messy middle.

Our hope is that the industry continues to invest in large scale, objective data about social impact, and to utilise these data to allocate capital and drive improvement. This sort of data is foundational for microfinance institutions, their investors, and to regulators as a starting point to know what is going on for clients, at both an absolute and relative level.

We shouldn’t be surprised that giving a small loan to a marginalised, often low-income customer has the potential to be transformationally positive; to have little impact; or to cause that borrower to fall into a debt spiral. The difference in those outcomes will be the result of how that loan is given, with what supporting services, and how the institution prioritizes client success and well-being versus maximizing short-term profits.

This kind of story might not make for attention-grabbing headlines, but it is an accurate picture of the challenge, and opportunity, to create meaningful, positive financial inclusion for those left out of the modern financial system.

Sasha is Co-Founder and CEO of 60 Decibels, a tech-powered impact measurement company that helps organizations to tap into high-quality, benchmarked customer insights. With thousands of impact measurement projects delivered worldwide, 60 Decibels proprietary Lean Data approach brings customer-centricity, speed and efficiency to impact measurement. Prior to co-founding 60 Decibels, Sasha worked for 12 years at the social impact investor Acumen. He’d previously worked at GE Capital, IBM, and Booz Allen.